Sign In

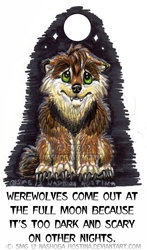

CloseI am fascinated by many ancient styles, such as those of the Haida Indians, the Aztecs and Mayans, ancient cave paintings from all across Europe, and, of course, the Celts. Being a wee bit Irish, I have some extra interest in the latter. Ireland was one of the last strongholds of the Celtic peoples, and as such, this country is often associated with them, and Celtic art had a strong influence upon the holy books written after their fall, the pages often adorned with highly stylized animals and mathematical Celtic knots. However, the Celts were once widespread, and you can see their influence on other places, particularly in the art of the Norse. This piece, however, is certainly not to be taken as an ‘authentic’ representation of Celtic styling. I took liberties as according to my own tastes, such as with the fur. Oftentimes, in Celtic art, long fur was indicated by curls, or almost scale-like patterns, not zigzags, and proportions were… well, sometimes a bit lacking. So, I switched up what I felt like.

Now, regarding the subject matter… While they’re no longer there, Ireland was once a stronghold of wolves. In fact, it was sometimes called “Wolfland.” However, though they were wiped out in 1786, not all tales involving Irish wolves were terrifying. In fact, Saint Albeus was, according to legend, suckled by a she-wolf after being abandoned. (Speaking of Saints, one of the places where the cynocephalic St. Christopher was best known of was in, you guessed it: Ireland.) Though, as is to be expected with any country with an abundant predator, stories were told of them.. in this case, werewolf stories.

You all have heard me talk about Saint Patrick before. According to some sources, he had the ability to turn people into wolves. The most told story about this is how he turned the King Vereticus into a wolf, however, in some accounts, he is also credited for cursing the people of Ossory with a form of lycanthropy that lasted many years. From what I can tell, the earliest account which does this is the Kongs Skuggio. However, more commonly, this transformative curse is attributed to Saint Natalis. Regardless of saint, the story goes that one of these holy men approached a group of people as they were holding an assembly and began to preach. Now, to be honest, it seems a tad rude to barge in on other people’s business, however they took his counsel anyway, but responded to him by howling like wolves. In his anger, he asked God to punish them, and they became werewolves.

People who were afflicted with this curse were similar to Greek and Polish werewolves in that they stayed wolves for great lengths of time… in this case, seven years. However, that is only unless they refrained from eating human flesh. If they dined on people, they were doomed to be wolves forever.

One interesting Ossorian tale is related to us by Giraldus Cambrensis’ Topigraphica Hibernica. In this tale, A Traveling priest is confronted by a wolf, who reveals himself to be a werewolf. He asks the priest to perform the last sacrament on his wife, who is dieing. The problem is that his wife is also a werewolf, and the priest is rather concerned about performing the final rights for an animal. The husband wolf peels away his wife’s wolf-pelt, and reveals a woman underneath. This convinces the priest, and after receiving the final sacrament, the she-wolf expires peacefully, while the husband went on to finish his years remaining in wolf-form. This, of course, caused a certain amount of debate and conflict amongst those who heard it.

Contradictorily, a few hundred years ago, Fynes Moryson reported that the Irish turned into wolves yearly, and according to Mr. Ashley’s book on the subject, those in Ossory considered themselves to be descended from wolves.

Now, you might be thinking that this sounds like there might have been practices of lycanthropy before the Christians arrived, and the folklore of the area was appropriated and modified in order to suit the new establishment. This is possible, especially since, according to the Leabhar Na H-Uidhri the druids that lived there practiced shapeshifting traditions.

This is supported by another tale: It is said that in Ireland, lycanthropy was hereditary, and that those of certain lineages could shift into faelad, that is, wolf-shapes. The most famous of these lycanthropes were of the Laignech Faelad, otherwise known as “The Wolf Men of Tipperary.” These were fearsome warriors who, howling like wolves, fought for the ancient kings of Ireland, and were every bit as fierce and ferocious as the beasts they assumed the shape of. They lived in remote areas, and unlike the werewolves of Ossory, they could turn into wolves whenever they wanted!

However… whether or not these inspired the tales from Ossory and such, I’m afraid I don’t know.

Ireland has such rich folklore and beautiful art, I cannot even begin to start praising it properly. So, for the understatement of the year: Irish stuff is cool. You ought to go check some of it out. In fact, here’s some books for you to look into, that helped me in making this:

The books of Durrow, Dimma and, of course, Kells,

The Wonders of Ireland – P.W. Joyce

159 Celtic Designs -- Amy L. Lusebrink

Celtic Beasts -- Courtney Davis

Celtic Design: Animal Patterns -- Adrian Meehan

Werewolves --Dr. Bob Curran

Werewolves -- Zachary Graves

The Beast Within --Adam Douglas

The Werewolf in Lore and Legend --Montague Summers

The Complete Book of Werewolves --Leonard Ashley

True Werewolves of History -- Donald F. Glut

Werewolves: The Occult Truth – Konstantinos

The Werewolf Book --Brad Steiger

Postscript: I know, the gallery has been almost all werewolves lately. I’m sorry, I’ve just been in a bit of an slump lately, and werewolves are a comfortable subject for me. I will probably redo this sometime later (with better Celtic knots.). But, for now it will do. Also, Apologies if I botched up the text.

Submission Information

- Views:

- 1017

- Comments:

- 0

- Favorites:

- 10

- Rating:

- General

- Category:

- Visual / Digital