Sign In

Close(Quick Note: I meant to include maps for the Schlieffen Plan in the last post, but I couldn't find my Kindle which contained links to the maps. Here's the website for Holger Herwig's book The Marne 1914: http://rhlink.com/marnemain)

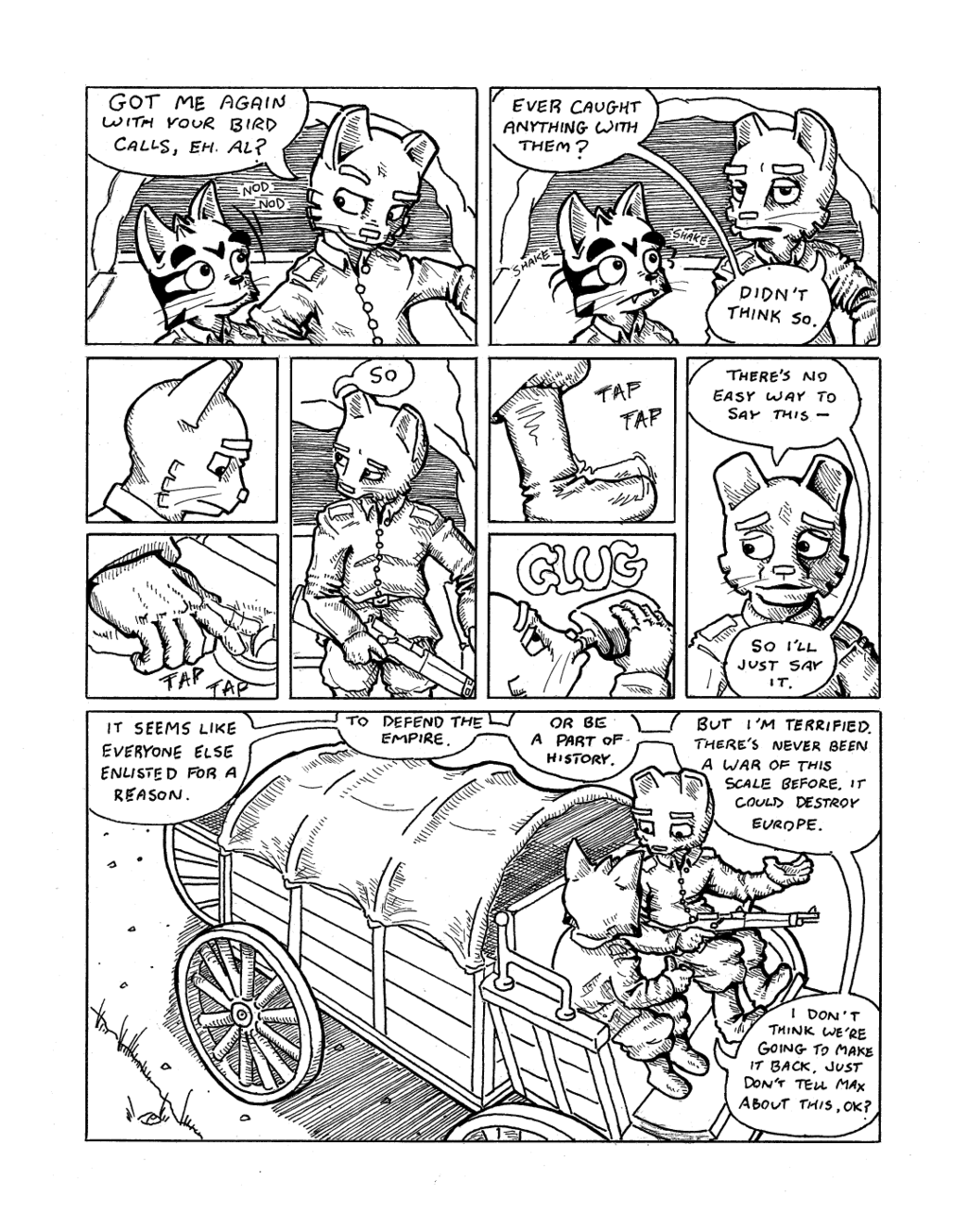

Eh, I guess the dialogue in this page isn't killer, but look at that wheel in the last frame. You know how many times I had to redraw that thing?

Anyway, what did Europeans think about the prospect of war in the lead-up to August 1914? I think our collective conscious tells us that people living in Europe in the nineteenth century were nationalists and mitarists. They took excessive pride in their countries' achievements and saw potential rivals or enemies all around them. But is this accurate?

First, to understand these attitudes we need some context. By the late nineteenth century a number of advances in science, technology, and medicine had transformed European civilization. Advances in medicine and agriculture improved European diets, exploded populations, and produced more robust, nourished adults. This is one reason nations were able to draw on large pools of manpower by 1914 and field million-man armies. Advances in weapons technology produced deadlier weapons in greater numbers than ever before. Like today, arms manufacturing also employed a lot of people (the Krupp works in Germany were one of the largest employers in the country). New types of artillery, dreadnoughts, machine guns, and asphyxiating gas were all recent developments. These advances changed the way nations and their leaders thought about war; the large reserves of manpower and efficiency of their new weapons gave them confidence that any war that broke out would be over shortly. Some people thought that a general European war was no longer possible; Europe was too advanced and civilized, and trade was too interconnected for any country to risk a war – it would disrupt the global economy.

Others looked forward to war. The pre-war world was full of writers, musicians, poets, artists, citizens, statesmen, and military leaders extolling the virtues of a general conflict among the great powers. Militarists felt that it brought out the best in people. The advances listed above had given people too many comforts, it made Europeans weak, soft, decadent. In their eyes conflict had the opposite effect; it created courageous, hard-working, disciplined people. So for some a general war was a way of strengthening the morals and values of European citizenry. For specific nations, the next big war was also their chance to change things in their favour. For England, the status quo was fine, but Germany threatened the balance of power on land and at sea. For Germany, “the day” (as it was called) would finally allow their little empire to dominate the continent and have its “day in the sun.” The French energetically looked forward to getting back Alsace and Lorraine. Military maneuvers were routinely carried out on the hills overlooking the region, with new recruits shown their country's lost land.

Not everyone looked forward to war. Indeed, many people looked around and were worried.

Friedrich Engels predicted that future wars would be “world wars” that would end with “famine, pestilence, and the general barbarization of both armies and people.”

There was an international peace movement that eventually culminated in the Hague Peace Conferences. Unfortunately, the nations that took part almost immediately shot down any attempts at banning warfare. Our good friend from my last post, Captain Mahan (author of The Influence of Sea Power on History), was part of the American delegation and would have nothing to do with disarmament.

“Our greatest and most dangerous foe,” Kaiser Wilhelm said of him.

The Peace Conferences accomplished little towards peace, instead setting out a few standards on conduct in war. Barbara Tuchman wrote about a situation where a ban on attacking or capturing commerce shipping was thwarted by the logic of a German delegate, despite the ban being “in the interests of humanity in general” according to the German foreign minister, Bulow. Here it is in full from The Proud Tower:

“Both were pulled up short by their own naval delegate, Captain Siegel, whose reasoning suggested the mind of a chess-player trained by a Jesuit. The purpose of a navy, he pointed out to his government, was to protect the seaborne commerce of its country. If the immunity of private property were accepted, the Navy's occupation would be gone. The public would demand reduction in warships and refuse to support naval appropriations in the Reichstag.”

The last group I'd like to mention is the one that would actually end up enlisting and fighting in the Great War. There was certainly no shortage of volunteers and many willingly went to war. Why did they enlist? In Potsdam a psychologist named Paul Plaut surveyed young German men with this question in mind, and the answers aren't too far from what a lot of young men would say today at recruiting centres. Some wanted to be a part of history in the making. Some wanted to prove their “manliness.” Others claimed it was their civic duty, they were defending the nation. Most did it to escape the boredom and monotony of everyday life. Interestingly, very few did it out of some form of hatred for another country. In France and England young men were just as enthusiastic about enlistment. Most people remember the “pals” battalions in England, where the army would allow friends and clubs to sign up and fight together.

These attitudes also need to take into account demographic factors like age, gender, class, and geography. It turns out that the “war euphoria” of 1914 depends a lot on this. The most enthusiastic parts of the population tended to be be in urban areas, and come from the professional and middle classes. Often they were men. In rural areas, citizens were much less inclined to support the war, especially at the end of July. Fruit was ripening, and wheat was almost ready for harvest. The countryside would need its young men to work on the farms. The pro-war crowds in Germany numbered less than 1% of their cities' populations, and anti-war demonstrations outnumbered pro-war ones in the days before the Great War broke out. From Holger Herwig's The Marne 1914:

“On the day Vienna declared war on Belgrade, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in Berlin turned out a hundred thousand antiwar protesters. By 31 July, there had taken place 288 antiwar demonstrations throughout Germany, involving some 750,000 people in 183 cities and villages. In Paris, Socialists and Syndicalists mounted seventy-nine demonstrations against the war.”

Finally, and perhaps most relevantly for this comic page, not every soldier looked at the coming war with enthusiasm. I'll end this post with a quote, again from The Marne 1914:

“Reservists, who had some inkling of what was to come, largely were apprehensive. Wilhelm Schulin, with 29th ID in Wurttemberg, on 1 August recorded 'incredible tension' among the people of his native Ohringen, which quickly turned to 'something horribly heavy, dark, a depressing burden' as the troop transports headed for the front. Martin Nestler at Chemnitz noted that the reservists of Saxon 12th Jager 'wept' as they reported for duty.”

Submission Information

- Views:

- 431

- Comments:

- 3

- Favorites:

- 0

- Rating:

- General

- Category:

- Visual / Traditional

Comments

-

-

I mean, the central powers weren't exactly innocent either, and the very next line after that quoted Socialist and Syndicalist paragraph was "But in the end, all 110 SPD Reichstag deputies voted for war credits, as did all 98 Socialist deputies in Paris. Party solidarity and patriotism counted for more than Socialist rhetoric." But I hope I complicated the situation a bit with the stuff I wrote.

That's really interesting, are you in Russia or somewhere in the Balkans? And I agree, history education here in Canada is pretty bad too. We learn very little about the rest of the world outside North America and Western Europe.

-

Link

kishniev

Ha, they never pointed that out in my school. For all we knew, Austro-Hungarians were the blood-thirsty genocidal meat grinder, not a nation but a Teutonic hive mind obsessed with drang nach Osten.