Sign In

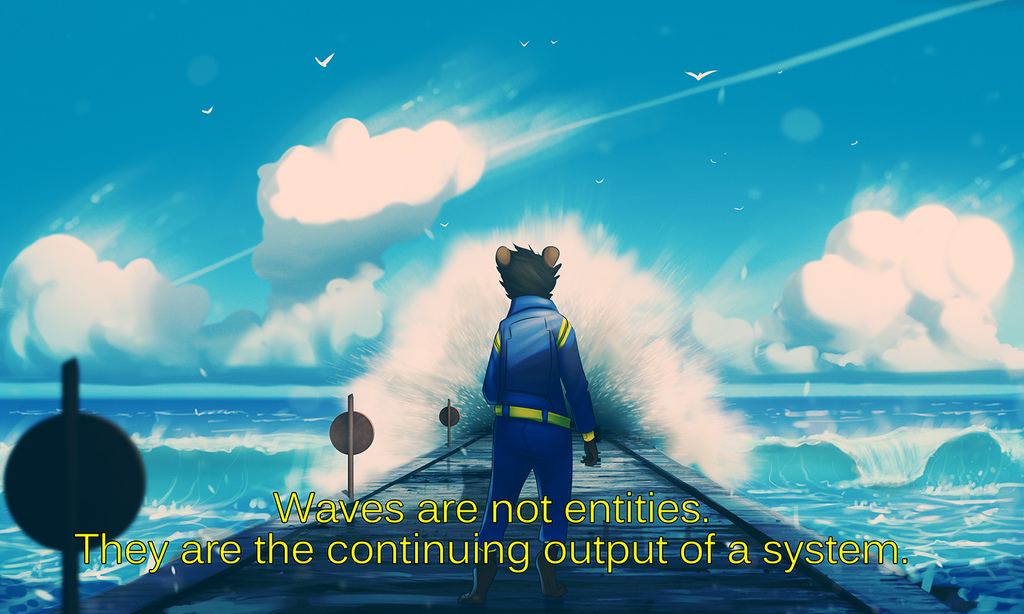

CloseAlthough we may recognize the systemic nature of the world, and would agree when challenged that something we normally think of as an entity is actually a system, our culture does not propound this insight as particularly interesting or profitable to contemplate. Let me propose to you a little exercise, taking the bay I am looking at now as a convenient example. It is not difficult to recognize that the movement of water in this bay is the visible behaviour of a dynamic system: after all, the waves are steadily moving in and dissipating themselves along the shore. But please consider just one wave. We think of that as an entity: a wave, we say. What is it doing out there, why is it that shape, and what is the reason for its happy white crest? The exercise is to ask yourself in all honesty not whether you know the answers, because that would be just a technical exercise, but whether these are the sorts of question that have ever arisen for you. The point is that the questions themselves—and not just the answers—can be understood only when we stop thinking of the wave as an entity. As long as it is an entity, we tend to say well, waves are like that: the facts that our wave is out there moving across the bay, has that shape and a happy white crest, are the signs that tell me “It’s a wave”—just as the fact that a book is red and no other colour is a sign that tells me “That’s the book I want”.

The truth is, however, that the book is red because someone gave it a red cover when he might just as well have made it green; whereas the wave cannot be other than it is because a wave is a dynamic system. It consists of flows of water, which are its parts, and the relations between those flows, which are governed by the natural laws of systems of water that are investigated by the science of hydrodynamics. The appearances of the wave, its shape and the happy white crest, are actually outputs of this system. They are what they are because the system is organized in the way that it is, and this organization produces an inescapable kind of behaviour. The cross-section of the wave is parabolic, having two basic forms, the one dominating at the open-sea stage of the wave, and the other dominating later. As the second form is produced from the first, there is a moment when the wave holds the two forms: it has at this moment a wedge shape of 120°. And at this point, as the second form takes over, the wave begins to break—hence the happy white crest.

Now in terms of the dynamic system that we call a wave, the happy white crest is not at all the pretty sign by which what we first called an entity signalizes its existence. For the wave, that crest is its personal catastrophe. What has happened is that the wave has a systemic conflict within it determined by its form of organization, and that this has produced a phase of instability. The happy white crest is the mark of doom upon the wave, because the instability feeds upon itself; and the catastrophic collapse of the wave is an inevitable output of the system. I am asking “Did you know?” Not “did you know about theoretic hydrodynamics?” but “did you know that a wave is a dynamic system in catastrophe, as a result of its internal organizational instability?"

Stafford Beer, "Designing Freedom" (1974)

Submission Information

- Views:

- 642

- Comments:

- 1

- Favorites:

- 27

- Rating:

- General

- Category:

- Visual / Digital

Link

barrakoda

The catharsis as a child learning that a "blade" of grass was not the wavelike movement of all grass moving in unison to a breeze but rather one single particular instance of grass.